HTM Sequence Memory and Cortical Layers

Numenta’s HTM theory includes a detailed explanation for the role of neurons and minicolumns in cortical layers. We’ve been sharing this theory for years and publishing implementations in our open source project, NuPIC. The best description of this theory is in the following papers:

- Why Neurons Have Thousands of Synapses, A Theory of Sequence Memory in Neocortex [1]

- A Theory of How Columns in the Neocortex Enable Learning the Structure of the World [2]

In the sequence memory paper, we’ve shown how the properties and organization of neurons in a cortical layer result in a powerful sequence memory that can learn to recognize high order sequences. Additionally, we’ve shown in the columns paper how an output layer in the cortex can learn patterns and recognize them in the future. This process results in stable activity in the output layer once a sequence or object is recognized.

New Study Consistent with HTM Theory

Our model for the function of cortical minicolumns gained some experimental support recently from work done by Homann, et. al. [3] in Michael Berry’s lab at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute. In their paper, they describe their experimental setup designed to test how mice responded to familiar vs. novel stimuli. This consisted of various experiments where the mice were repeatedly presented with temporal sequences that varied in length. After some number of repetitions of the sequence, one or more images would be replaced with a novel image.

By recording the neural activity in the visual processing region V1, the experimenters were able to identify several classes of neural activity:

- The transient response – A majority of neurons showed an increase in firing rate in response to the novel images substituted into the repeated patterns. Additionally, the first few images in the initial presentation of a sequence showed a similar increase in neuron activity.

- The sustained periodic response – A small number of neurons showed a sustained response during a sequence. These cells were active during a specific portion of the sequence and, in some cases, also active during the transient periods.

- The maintained response – These were similar to the sustained periodic neurons but maintained activity throughout the entirety of the sequence rather than responding only during a specific portion of the sequence.

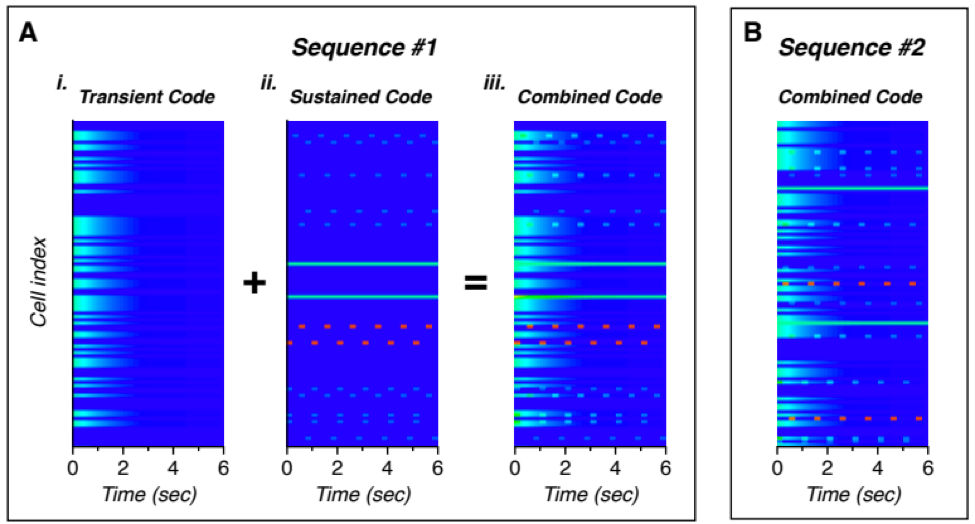

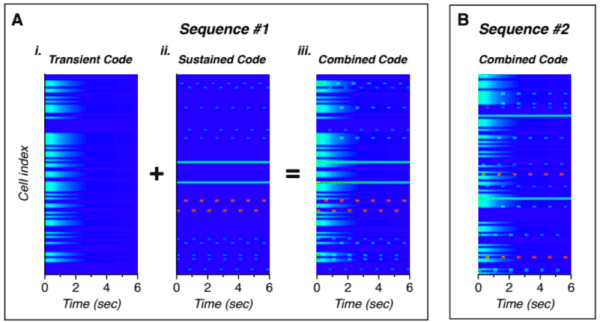

Figure 1. The neural activity over time for two sequences, A and B. For sequence A, the transient and sustained codes (far left) are shown separately for illustration. The combined code that matches the recorded data follows. While the structure of the code for sequence B is similar, the individual cells that represent the transient and sustained codes differs [3].

These results very closely match predictions from our theory. Our theory states that the cells within a minicolumn share a receptive field and all become active during unpredicted events. This explains the increased transient response both at the beginning of a sequence as well as for novel substituted images.

Additionally, our theory says that cells within the minicolumn encode the temporal context and that during a learned sequence, only the cells that represent that context are active and predict the next set of cells in the sequence. This is consistent with the sustained periodic response neurons that additionally fire during the transient periods.

The final population identified in the paper – the maintained response neurons – can be explained by the output layer described in the columns paper [2]. The output layer learns to recognize sequences or objects. During recognized sequences, the output layer will exhibit stable activity, exactly like the maintained response found in the paper.

Interplay Between Theoretical and Experimental Neuroscience

Improved experimental techniques are providing new knowledge about the biology of the brain. This in turn helps drive more sophisticated theories that explain more of the function of the neocortex. Similarly, advances in neocortical theory help steer experimental work to relevant areas. This new paper is a great example of new techniques enabling experimental work that supports our theory.

We will continue to [publish our theory and predictions](/resources/papers/) and work with the broader scientific community to ensure these predictions are known and can be tested as they become technically viable to verify. One experimental setup is never enough to prove a theoretical prediction. Over time, we will be able to aggregate results from multiple experimentalists, and we will update our theory as new experimental data becomes available.

As such, HTM theory still has many unverified predictions about the structure and function of the neocortex. We would love to talk with more experimentalists that are interested in testing these predictions. Subutai shared the following list of predictions, verbatim, during his Cosyne workshop presentation [4] earlier this year, and we are eagerly awaiting additional experimental results to help us reconcile our understanding of the structure and function of the neocortex:

1. Sparser activations during a predictable sensory stream. [5]

2. For predictable natural stimuli, dendritic NMDA spikes (i.e. predictions) will be much more frequent than somatic action potentials. [6]

3. Correlation structure [7][8][9][10]:

- Low pair-wise correlations between cells but significant high-order correlations.

- High order assembly correlated with specific point in a predictable sequence.

- Unanticipated inputs lead to a burst of activity correlated vertically within mini-columns.

- Activity during predicted inputs will be a subset of activity during unpredicted inputs.

- Predictable inputs lead to negative correlations within mini-columns.

- Neighboring mini-columns will be uncorrelated.

4. Branch specific plasticity [11][12][13]:

- Strong LTP in dendritic segments: NMDA spike followed by back action potential (bAP).

- Weak LTP (without NMDA spike) if synapse cluster becomes active followed by a bAP.

- Weak LTD when an NMDA spike is not followed by an action potential/bAP.

5. Depolarized cells need fast inhibition to inhibit nearby cells within mini-column.

References

[1] Hawkins, J., & Ahmad, S. (2016). Why Neurons Have Thousands of Synapses, a Theory of Sequence Memory in Neocortex. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 10(23), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2016.00023

[2] Hawkins, J., Ahmad, S., & Cui, Y. (2017). A Theory of How Columns in the Neocortex Enable Learning the Structure of the World. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, doi: 10.3389/fncir.2017.00081

[3] Homann, J., Koay, S. A., Glidden, A. M., Tank, D. W., & Berry, M. J. (2017). Predictive Coding of Novel versus Familiar Stimuli in the Primary Visual Cortex. bioRxiv, 197608. https://doi.org/10.1101/197608

[4] Ahmad, S. (2017). “Why Do Neurons Have Thousands of Synapses? A Theory of Sequence Learning in Neocortex.” Computational and Systems Neuroscience (Cosyne) 2017.

[5] Vinje, W., Gallant, J. (2002). Natural stimulation of the nonclassical receptive field increases information transmission efficiency in V1. J Neurosci. 2002 Apr 1;22(7):2904-15.

[6] Smith, S., Smith, I., Branco, T., Häusser, M. (2013). Dendritic spikes enhance stimulus selectivity in cortical neurons in vivo. Nature, doi:10.1038/nature12600

[7] Ecker et al. (2010). Decorrelated neuronal firing in cortical microcircuits. Science 29 Jan 2010: Vol. 327, Issue 5965, pp. 584-587. doi: 10.1126/science.1179867

[8] Smith, S., Häusser, M. (2010) Parallel processing of visual space by neighboring neurons in mouse visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010 Sep;13(9):1144-9. doi: 10.1038/nn.2620. Epub 2010 Aug 15.

[9] Schneidman E., Berry, M., Segev, R., & Bialek W. (2006). Weak pairwise correlations imply strongly correlated network states in a neural population. Nature. 2006 Apr 20;440(7087):1007-12. Epub 2006 Apr 9.

[10] Miller, J., Ayzenshtat, I., Carrillo-Reid, L., & Yuste, R. (2014) Visual stimuli recruit intrinsically generated cortical ensembles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. E4053–E4061, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406077111.

[11] Losonczy, A., Makara, J. & Magee, J. (2008). Compartmentalized dendritic plasticity and input feature storage in neurons. Nature 452, 436-441. doi:10.1038/nature06725

[12] Yang et al. (2014). Lactate promotes plasticity gene expression by potentiating NMDA signaling in neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Vol. 111 no. 33. 12228–12233, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322912111.

[13] Cichon, J. & Gan, W. (2015). Branch-specific dendritic Ca2+ spikes cause persistent synaptic plasticity. Nature 520, 180–185. doi:10.1038/nature14251.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Subutai Ahmad, Matt Taylor, and Christy Maver for their reviews and input on this post.